What's up with the blackout? Experiences of censorship in Latin America

"I can't upload this video", "they deleted my post because it's considered 'sensitive content'," "they closed my account" or "I lost my connection" are some of the requests for help repeatedly heard in different parts of Latin America. The focused censorship has been notable during the enormous social upheavals that continue today with massive street demonstrations and the strong participation of feminist groups.What do these recurring attacks on our communications mean? How can we document and monitor them? In this post we try to answer the question "What is going on with the blackout?"

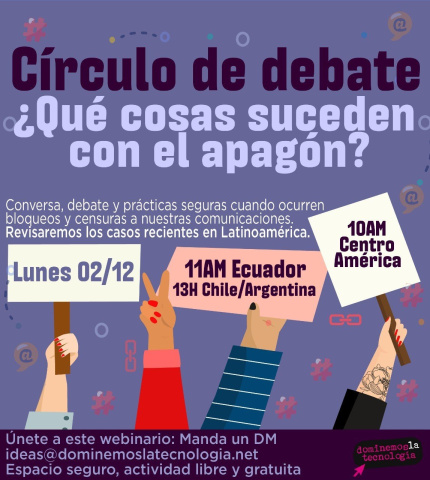

The Take Back the Tech! campaign in the context of the 16 days of activism (November 25 to December 10) called out all those attempts to silence us, block off our public streets and our right to assembly on the internet. Like when they charge us with defamation instead of scrutinizing our attackers, close our accounts or take down our posts because they mysteriously don't fit community standards. In this blog we will find common ground when state violence escalates, as well as share good practices for protecting dissenting voices.

The context requires that we talk about attacks on freedom of expression mediated (or not) by technologies. There are not enough eyes or emotional resistance to process the levels of violence provided by the news we receive about the mobilizations (and the subsequent violent repression) in countries like Ecuador, Chile, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Colombia. The private social networks, despite their sexist and patriarchal algorithmic bias, allow us to see the visual testimonies recorded by people with cell phones in hand. The street demonstrations and speaking out, still possible on a hyper-commercial internet, give us strength to continue on.

We learned from the report by the Fundación Datos Protegidos (Protected Data Foundation) and the Observatorio del Derecho a la Comunicación (Observatory of the Right to Communication) in Chile, as well as the publication by APC, Digital Defenders Partnership (DDP), LaLibre.net Tecnologías Comunitarias, and Taller de Comunicación Mujer about internet blackouts and the variety of ways that censorship manifested itself. Civil society organizations with links to community organizations and academia are key players in documenting the disruptions in the flow of information.

Attacks on freedom of speech - a right that makes possible the vital act of providing one's own version of events - have taken different shapes such as a direct attack by a member of the military on a demonstrator's cell phone, the blocking of a Twitter account, the removal of a post on Facebook and the blocking of a cell phone that at the least expected moment loses its signal.

"The right to protest and freedom of expression are two closely linked rights. Therefore, disruptions in internet communications in the form of blackouts and restrictions constitute direct censorship of the public and are factors that restrict the exercise of fundamental rights," stresses the report that describes the blackouts experienced in Ecuador. These fundamental rights need to be reaffirmed, which is why on December 2 more than 20 people gathered in a secure VoIP platform to share experiences from different areas, and to discuss good practices in the identification of anomalies and censorship, as well as the safeguarding of our information.

Organizing chaos

In order to give shape to the concerns, doubts and interest in wanting to know how to act, and to analyze how to organize ourselves in the midst of the chaos, violence and confusion occurring in our cities and countries in Latin America with regard to this issue, we invited Patricia Peña, of Datos Protegidos and the University of Chile; Pilar Sáenz of Karisma, in Colombia; Anais Córdova Páez from the Taller de Comunicación Mujeres in Ecuador; and Damaris Mendoza, a consultant and defender of online rights from Nicaragua.

In this section we will highlight only some parts of the conversation in order to underscore the observations that the activists made about the most serious disruptions seen in their countries. They reveal a similar scenario in which violations of civil liberties converge in curfews or states of siege and, fundamentally, in which the methods to silence people vary and the levels of technologies involved (whether to censor or be censored) differ according to context.

Chile

Patricia Peña gave a brief account of the events that began on October 18 with mass demonstrations by students against the subway fare hike in Santiago, Chile. The government responded with a harsh crackdown and a curfew: "At first we were afraid that access to internet would be affected by the curfew, which was to last six nights. The traffic over the social networks and Whatsapp became intense. On the first weekend people began to tell us things like 'I'm trying to post something and I can't' on different social networks (Instagram and Facebook in particular). What was being shared over the social networks at the time was shocking information related to arrests, with police forces shooting their way into many towns, and the military in the streets."

After about 100 cases reporting content loading anomalies, the Datos Protegidos (Protected Data) organization created a questionnaire. Peña said the questionnaire began to be sent to feminist groups and community media outlets that reported cases ranging from "I can't access the account," "I can't see what my friends are posting," to "I can't post something." The things people were unable to post ranged from an important video showing what "could have been a 'carabinero' (police officer) opening fire in a town, or footage showing someone being arrested and taken away that night. This happened to high school students. Besides, all this information documented cases, it was material that could be used to support legal complaints and cases."

The organization tried to get an idea about who was practicing the censorship, since it was not necessarily clear who was censoring the social networks. "Is it the government? Does this have to do with explicit censorship? By whom? It was important to have the ability to contact social media platforms to understand the nature of these types of incidents," Peña explained.

Lessons learned

- The importance of systematizing / working collectively and collaboratively to document incidents.

- The platforms responded to the complaints about censored content (conversations were held with Facebook, Twitter, Instagram).

- Continue to work with groups: although there is a much greater awareness than there was a month ago that we have to protect equipment and devices, this is a moment that offers an opportunity to come together to document incidents and offer work on the ground and support in areas where there is an urgent need.

- Gradual work encrypting communications and files.

Ecuador

Anais Córdova Páez said the social upheaval in Ecuador was triggered on October 2 when the government presented decree 883, aimed at ending subsidies on gasoline. It also undermined labor rights, among other prescriptions from the International Monetary Fund for Latin America. On October 2-3, a transportation strike was called to protest the removal of gasoline subsidies. Shortly thereafter, an organization that included groups from all over Ecuador began to emerge, and indigenous organizations converged on the capital as part of a social uprising on a scale not seen since 1989.

"On October 6 a report was issued by the Netblocks organization, that was the day of the first complaint about restrictions on the signal. This first report shows us that on this day, when all the indigenous organizations were in Quito, things were clearly organized in the streets so the blackouts began."

Organizations that defend the right to communication decided, according to Córdova Páez, to monitor what was happening. This included going in person to the areas of greatest conflict to verify the lack of telephone and internet signal and to study the censorship on the ground. "We were seeing several casualties in relation to community and alternative media. Not only were their websites shut down but there was a lot of censorship and a great deal of content was removed. But something that triggered the first blackout was the murder of a student by the police, and from that point on many people started to organize, to react, to realize that the police repression was extremely harsh, very different from previous occasions."

Ecuadorian organizations also reported a lack of access to communications within hospitals and universities, in places where the indigenous movement was marching to demand their rights, and in facilities that gave assistance to people injured in the mobilization, where communication is essential to provide services.

"The next major blackout was on the 10th when a big march was called. It was organized by the indigenous movement of the Sierra (the highlands), as well as the indigenous movement of the Amazon rainforest and several other organizations. As a result, there was heavy repression. The next day at a funeral mass that paid tribute to all the people who were killed during the strike, held at the Agora of the House of Culture, there was a complete communications blackout for all the people who were there and nearby. There was a signal just a few kilometers away. That frightened people. They understood that the danger was imminent, real, that there was a blackout, first by the CNT (the national telephone company) and then by the Claro (cell-phone network) company."

In the view of Córdova Páez and the organizations that mapped the blackouts in Ecuador, the most serious aspect of the matter was the violation of the right to be informed, especially at a time when there are waves of misinformation, aggravated by blockages of other complementary services.

Lessons learned

- The importance of having website infrastructure to back up information. The implementation of this infrastructure implies a significant effort in terms of support and follow-up.

- Keep systematic logs of unfortunate events. In addition to the possible use of Ooni (a Tor Project tool that allows you to detect traffic manipulation on the internet), among other tools you can use, such as simple paper notebooks and/or excel spreadsheets.

- Learn from the women's rights movement and how these teachings can be applied in cases of violations of digital rights.

- Take into account the possible out-of-date nature of equipment and cell phones depending on the different communities with which one works. Provide support and updates.

Colombia

Colombia has been experiencing a moment of “acute mobilization” since November 21, said Pilar Sáenz of Fundación Karisma. "The call for this mobilization came from trade unions, student groups and indigenous organizations because the government's policies have not lived up to the expectations surrounding the peace accords. In many respects, the conditions in terms of health, work and education are not the best.”

The peace agreements reached in recent years have not been fulfilled in terms of budget, projects and programs that would translate into an improvement of the quality of life of the entire population and of specific vulnerable groups such as the victims of the armed conflict especially, or students, indigenous people, peasant farmers, and black people. The level of participation in the demonstrations by residents of major cities has been unprecedented in Colombia, and they held their first "cacerolazo" or pot-banging protest on November 21.

Sáenz reported that there had previously been a large government campaign against the protest. A curfew was also declared in parts of Colombia. "On November 21 for the first time in many years a curfew was declared in a capital city: Cali. On November 22 a curfew was declared in Bogotá, where there had been no curfew since the 1970s."

With respect to signal blackouts, Sáenz noted that no major internet blockages had been reported up to the time of this conversation. However, the situation is different in the case of proprietary social networks: "There are reports that it is much more difficult to access Facebook, and at times Twitter, but there is no verifiable blockage that we have accurate data about. What we have seen are specific problems with content that has been removed by social networks, particularly Facebook, after classifying it as 'sensitive content' and preventing people who had shared this content from taking part in the conversation on social networks and from posting from their accounts.”

This panorama also poses problems and challenges for freedom of expression because it shows that the platforms based in Silicon Valley are making decisions to prevent the circulation of certain information. The rules according to which this information is omitted are still unclear."We have not yet found a way to question how the platforms make decisions about content and about people, with the effects this has on so much information circulating in the country," said the Karisma activist.

Lessons learned

- Make the effort to document and report proven incidents.

- Continue to demand that platforms publicly provide reasons why they censor and/or block content.

- Review transparency reports from proprietary platforms to see if they reflect our governments' requests for content censorship.

Nicaragua

In the case of Nicaragua, repression by the government of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo has already caused the deaths of more than 300 people, while hundreds of people are missing or deprived of their freedom without just cause.

The crisis, which broke out as a result of the social discontent that the public has been experiencing for years under the FSLN government, went far beyond failing to guarantee compliance with and respect for human rights: repression, physical aggression and psychological fear were used to try to restore order and squelch social protest. The networks were filled with memes, hashtags and the well-known photo and poster supports from all over the world. Flyers were also distributed with concrete evidence of people - students and activists in particular - who were being seized and taken away in broad daylight.

Damaris Rivera Mendoza, a digital rights defender and digital security trainer, said that in March 2018 there was an attempt by the government to impose a "gag law" in order to censor social networks. "The ruse was to use the Family Code, under the guise of protecting children and young people from cyberbullying and/or cyberharassment: the facade was to try to protect public security. To take a stand against 'rumours' that were destabilising the government. The law didn't pass in the legislature.”

However, Rivera Mendoza said that during the last few years, when the Ortega administration has had a heavy hand, censorship has expressed itself in a very specific manner. "What has been happening here in Nicaragua is a combination of technological and physical aspects. I understand that there is a team of trolls behind the presidential couple who, when they saw that the social networks were our means of expressing our freedom of speech about what was happening in Nicaragua, began to persecute us. This team follows everything that we Nicaraguans speak out about and publish on the networks, seeking to block our work on social and activist networks."

Rivera Mendoza talked about different strategies to hack into the Facebook accounts of the most influential people in the social networks. Another interesting fact that the activist highlighted involved the Citizen Power Councils active in every neighborhood and also at a departmental level. "In every neighborhood there are one or two people who report on what's going on in the neighborhood. The social networks are monitored, and this person keeps tabs on what everyone else is doing. Added to this is the question of the paramilitaries. Last Sunday an activist was besieged in her house by the police because she is influential in the social networks or in the few alternative radio stations that are still on the air. What I want to convey is that censorship is not only seen in the social networks, but is felt at home and in our neighborhoods, where we are constantly watched.”

Lessons learned

- Use of encrypted communications, TOR and VPNs.

- Promotion of training in digital security through workshops and on-site support in rural, urban and marginalised areas.

- Activists should not carry their "smart" phones when they go out to march. Rather, they should rely on the support of basic cell phones with minimal information, essential to avoiding exposure of contacts and personal information in case of arrest. p { margin-bottom: 0.1in; line-height: 115%; }a:link { }

- Log in to post comments