#SouthtoSouthSolidarity: Unpacking intersectional and international solidarity

Publié le : 17 December 2018

During #16daysofactivism 2018 the wonderful Take Back the Tech! team held a South to South Solidarity Tweetchat. This was an opportunity to begin to dissect intersectional and international solidarity. As a young black woman from the global North, this started with me sitting back, listening to and learning from allies and activists in the global South.

I think it’s safe to say the 90s is one of the best eras of all time. Not only did it give us the best Hip Hop and RnB music, I was born (#jokingnotjoking), and in 1992 there was a global call to mobilise against gender-based violence. The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence is an annual powerful moment to highlight and confront all forms of violence against women and girls. This ranges from domestic violence, sexual harassment at work and online gender-based abuse. With movements like #MeToo and Take Back the Tech! smashing away at patriarchy both offline and online, 16 Days has become even more important, yes in order to campaign but also to reflect, to share and to re-strategise, ensuring we remain intersectional and not passive allies.

It’s only in the law few years I’ve been involved in 16 Days; I don’t think it has as high a profile in the UK as it does in Latin America and the global South. Attending Take Back the Tech! Camp this summer in Nepal, hearing fellow activists plans and feeling the energy in that hot room, made feel like we were gearing up for International Women’s Day or an huge election campaign. It was super exciting! However, it made me wonder, “where is the same level of enthusiasm in the global North?” I mean, I may not have been invited to the planning party (awkward). Or maybe 16 Days means a whole lot more in the global South that we in the North take for granted?

I learnt many life-changing lessons at Take Back the Tech! Camp, intersectional and international solidarity being just one. As a young black British Nigerian woman I’m rarely in environments where I hold any relational privilege, so to be associated with the “global North” and the “privilege crew” was weird taste. The Camp provided an honest (and tough) space to for me to once check my privilege and understand that not all solutions to fixing the glitch of online abuse in the UK are suitable solutions for allies in the global South; and actually could do more damage than good. For instance, calling on the government for regulation and intervention.

I left Take Back The Tech! Camp with many new friends and a different perspective on 16 Days of Activism 2018, self-care, boundaries and international solidarity must be at its core. To quote the Goddess of intersectional feminist activism Audre Lorde, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” —Audre Lorde. So to hear that Take Back the Tech! team were holding a Tweetchat on South to South solidarity to mark 16 Days was my turn to practice what I continuously ask of those with privilege; to sit back and learn.

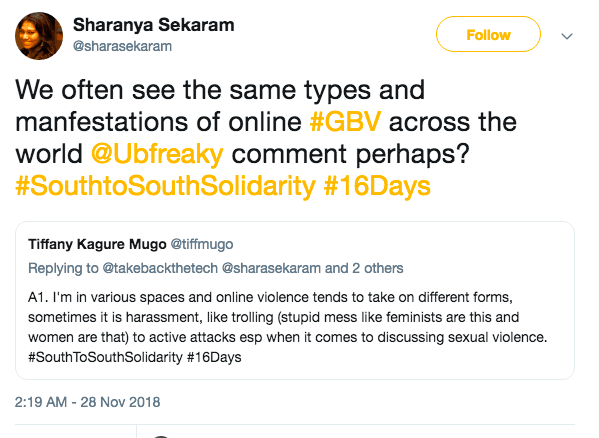

There were five strong activists from all over the global South taking time out of their insanely busy schedules to part in the hour long discussion. We heard from Tiffany Mugo from HOLA Africa based in South Africa and Kenya; Sharanya Sekaram Editor of Bakamoonolk based in Sri-Lanka; and writer Syar S. Alia based in Malaysia.

The fruitful discussion started with an outline of what online gender-based violence in each country looked like and there were many shared experiences and similarities. State and or institutional sponsored censorship and moral policing of behaviours was a common theme whether conducted by the state in Malaysia or religious institutions in Kenya and Sri Lanka.

One form of online abuse discussed which is also a huge problem in the UK, was abuse towards politically active women. Abuse “amounts not just to outright calls for violence but also attack on our dignity.” The United Nations call for gender equality is under threat if online abuse towards women human right defenders and female politicians is not urgently addressed in both a global and intersectional way.

Conversations moved on to general public awareness of online abuse and how it is discussed. Although there are different terms for online gender-based abuse, there was an agreed frustration with the narratives around online vs offline abuse and such discourse forcing a hierarchy around the forms of abuse women face, neither of which are at all helpful. Limiting the forms of online abuse women face in itself erases the experience women with multiple intersecting identities and from lower socio-economic classes battle. Therefore, there is a huge need for both local and global movements to deal with contextual issues, instigate a process of unlearning harmful behaviours and galvanise large numbers.

In our activism we respect and help facilitate more local and regional movements uniting around shared experiences and identity. For instance, as helpful as “women of colour” is, there are crucial times that only black women must meet, laugh, cry and organise in safe spaces. But to avoid creating an us and them within the global family, a topic to urgently be discussed is how local collectives connect with diaspora communities around the world and vice versa.

Not only do we need a range of accessible forums we need a range of language that does not erase the experiences of diaspora communities who certainly have some “relational” or “western” privilege but are also dealing with systematic racism, oppression and the organised far right movements. For those who have watched Black Panther, I always think back to the discussions around Wakanda being more open and working with diaspora communities in the United States.

To unpack intersectional and international solidarity our activism must create spaces to campaign AND reflect on our privilege. For us in the global North we must take more time to listen to how violence against women manifests itself in the South. Yes this is forced marriage, female genital mutilation but it also the abuse that doesn’t gain as much profile or UN funding. We must be mindful and critical of ourselves to not create technology and platforms that exacerbate inequalities in the global South nor push for government interventions that could increase censorship and violate other human rights.

Many many thanks to Tiffany Mugo, Sharanya Sekaram, Sanghapali Aruna and Syar S. Alia sharing your experiences, insights and resources.

Seyi Akiwowo is Executive Director of Glitch

I think it’s safe to say the 90s is one of the best eras of all time. Not only did it give us the best Hip Hop and RnB music, I was born (#jokingnotjoking), and in 1992 there was a global call to mobilise against gender-based violence. The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence is an annual powerful moment to highlight and confront all forms of violence against women and girls. This ranges from domestic violence, sexual harassment at work and online gender-based abuse. With movements like #MeToo and Take Back the Tech! smashing away at patriarchy both offline and online, 16 Days has become even more important, yes in order to campaign but also to reflect, to share and to re-strategise, ensuring we remain intersectional and not passive allies.

It’s only in the law few years I’ve been involved in 16 Days; I don’t think it has as high a profile in the UK as it does in Latin America and the global South. Attending Take Back the Tech! Camp this summer in Nepal, hearing fellow activists plans and feeling the energy in that hot room, made feel like we were gearing up for International Women’s Day or an huge election campaign. It was super exciting! However, it made me wonder, “where is the same level of enthusiasm in the global North?” I mean, I may not have been invited to the planning party (awkward). Or maybe 16 Days means a whole lot more in the global South that we in the North take for granted?

I learnt many life-changing lessons at Take Back the Tech! Camp, intersectional and international solidarity being just one. As a young black British Nigerian woman I’m rarely in environments where I hold any relational privilege, so to be associated with the “global North” and the “privilege crew” was weird taste. The Camp provided an honest (and tough) space to for me to once check my privilege and understand that not all solutions to fixing the glitch of online abuse in the UK are suitable solutions for allies in the global South; and actually could do more damage than good. For instance, calling on the government for regulation and intervention.

I left Take Back The Tech! Camp with many new friends and a different perspective on 16 Days of Activism 2018, self-care, boundaries and international solidarity must be at its core. To quote the Goddess of intersectional feminist activism Audre Lorde, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” —Audre Lorde. So to hear that Take Back the Tech! team were holding a Tweetchat on South to South solidarity to mark 16 Days was my turn to practice what I continuously ask of those with privilege; to sit back and learn.

There were five strong activists from all over the global South taking time out of their insanely busy schedules to part in the hour long discussion. We heard from Tiffany Mugo from HOLA Africa based in South Africa and Kenya; Sharanya Sekaram Editor of Bakamoonolk based in Sri-Lanka; and writer Syar S. Alia based in Malaysia.

The fruitful discussion started with an outline of what online gender-based violence in each country looked like and there were many shared experiences and similarities. State and or institutional sponsored censorship and moral policing of behaviours was a common theme whether conducted by the state in Malaysia or religious institutions in Kenya and Sri Lanka.

One form of online abuse discussed which is also a huge problem in the UK, was abuse towards politically active women. Abuse “amounts not just to outright calls for violence but also attack on our dignity.” The United Nations call for gender equality is under threat if online abuse towards women human right defenders and female politicians is not urgently addressed in both a global and intersectional way.

Conversations moved on to general public awareness of online abuse and how it is discussed. Although there are different terms for online gender-based abuse, there was an agreed frustration with the narratives around online vs offline abuse and such discourse forcing a hierarchy around the forms of abuse women face, neither of which are at all helpful. Limiting the forms of online abuse women face in itself erases the experience women with multiple intersecting identities and from lower socio-economic classes battle. Therefore, there is a huge need for both local and global movements to deal with contextual issues, instigate a process of unlearning harmful behaviours and galvanise large numbers.

In our activism we respect and help facilitate more local and regional movements uniting around shared experiences and identity. For instance, as helpful as “women of colour” is, there are crucial times that only black women must meet, laugh, cry and organise in safe spaces. But to avoid creating an us and them within the global family, a topic to urgently be discussed is how local collectives connect with diaspora communities around the world and vice versa.

Not only do we need a range of accessible forums we need a range of language that does not erase the experiences of diaspora communities who certainly have some “relational” or “western” privilege but are also dealing with systematic racism, oppression and the organised far right movements. For those who have watched Black Panther, I always think back to the discussions around Wakanda being more open and working with diaspora communities in the United States.

To unpack intersectional and international solidarity our activism must create spaces to campaign AND reflect on our privilege. For us in the global North we must take more time to listen to how violence against women manifests itself in the South. Yes this is forced marriage, female genital mutilation but it also the abuse that doesn’t gain as much profile or UN funding. We must be mindful and critical of ourselves to not create technology and platforms that exacerbate inequalities in the global South nor push for government interventions that could increase censorship and violate other human rights.

Many many thanks to Tiffany Mugo, Sharanya Sekaram, Sanghapali Aruna and Syar S. Alia sharing your experiences, insights and resources.

Seyi Akiwowo is Executive Director of Glitch

- Log in to post comments