No Sweetness Here: Making a Feminist Internet — Africa and Its Afterlives

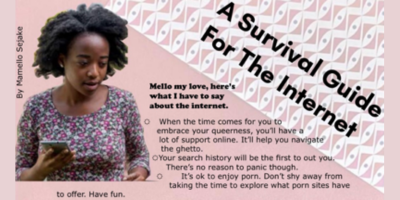

Image via Zine-ing a Feminist Internet

The zine-making collective ‘No Sweetness Here’ was formalised through the AWC-TBTT grant process. The collective consists of Youlendree Appasamy and Wairimu Muriithi. Wairimu, a feminist reader, writer, editor and curator of cool things whose areas of research and writing include crime and criminality, queer cultural production, freedom of expression and care-work in movement building. We were fortunate enough to get to speak to one half of the collective, Youlendree, who is a freelance writer and editor, working mainly in the South African media space. She is one of the inaugural ‘Africa is Country’ writing fellows and she’s part of a South African art collective called the ‘Kutti Collective’. She also makes beaded jewellery which she sells online and she describes herself as a “feminist free radical working in media and arts spaces”.

Youlendree and Wairimu worked on creatively documenting APC WRP’s Making a Feminist Internet: Africa gathering in 2019. They created an e-zine and when applying for this grant, they wanted to extend and expand both of their methodologies and thematics. They felt there were elements of feministing while African that weren’t covered in the first e-zine and they explored those issues further in the latest e-zine. The first edition was an experiment in creative rapporteuring of an event, containing profiles from feminists and published in the early days of the pandemic. This second edition was a continuation:

An archive in motion — In this edition, we centre the process of thinking towards models of care and repair. As artists and researchers, archiving has always been an important practice for us, particularly radicalised by the many instances we have not been able to find the stories we need and want where we were trained to look. The community we often turn to - particularly in this period of a global pandemic and its attendant lockdown measures - are the people we have known online and/or offline engaged in the same kind of intellectual and creative labour. We know that there is always more – so much more – to say and do about our lives and afterlives at the intersection of African feminisms, movement-building and accessible and inaccessible technology, and we wanted to see where more extensive conversations could take us when we turned towards our political blindspots and tended to our vulnerabilities with collective care.

There were three focus areas for this project titled Zine-ing a Feminist Internet. The first area was that of collaborative storytelling, using 10 Feminist Learning Circles to co-create with e-zine collaborators. They then moved on to basic design technology, learning about zine-making software like Scribus and Canva, as well as basic design principles using a design justice framework. One of the workshops was facilitated by Tiger Maramela, an independent artist and project consultant, emphasising digital collaging. The third area included the curation and publication of written and visual content and this was achieved through co-curation.

The completed project, ‘Making a Feminist Internet: Africa and Its Afterlives’ was published on Internet Archive and Issuu on 23 October 2020. This was a project steeped deeply in community, in ensuring the stories of communities that are often silenced are placed at the fore. It was an informal working space, prioritising friendships, placing importance on safety and collective care. What the collective wanted to guarantee is a process that documents their existences, work and desires, for themselves and for the people in the future they are actively trying to make a reality. To them, living a feminist politic means always trying to know more, do better, and actively find creative ways to enact those intentions.

The one thing the collective was really proud of is how this work managed to bring together a new community; all of the collaborators are engaged in feminist work in their own geographies and areas of advocacy. They commended the commitment to the project and the affinity between the collaborators.

Youlendree went on to say that seeing the whole thing come together, designing each page with the co-creators notes in mind and then sharing it with everyone was fantastic. On a personal growth note she says she and Wairimu taught themselves and each other about how to design accessibly. They were led by design justice principles and they figured out how to incorporate alt-text, pdf tagging and more into the e-zine.

One of their challenges apart from the difficulty of trying to coordinate time zones, work commitments and bouts of exhaustion was the global pandemic. Doing this work in a pandemic meant that their work needed to be responsive to technology and how they could better utilise it. They were also aware of their mental health and that of the co-creators and this meant deadlines were shifting targets. There was however a bright side, participants noted that because of South Africa’s Covid-19 lockdown, they were working from home and could attend e-zine making sessions and that this would have been harder to manage under non-pandemic conditions.

As artists and researchers, archiving is an important practice for them and even more so because there have been many instances where they have not been able to find the stories they need and want. The outcomes were strengthened voices and more connected communities of all women so that they can challenge norms, values and power structures to push back against violence against them. The other outcome was that all women are able to enjoy freedom and opportunities by being able to access and assert their rights to public spaces and resources.

Some of the topics covered in the zine were:

- Feminist Ecologies of the Internet, expanding and building cross-movement alliances.

- Ann Holland’s geode to sex chats, covering consent, contraceptives, body autonomy and sex.

- Case studies of what makes a Feminist Internet.

- A Guide to Accessing Mental Health Care written by Nyambura ‘Mike’ Mutanyi.

- Discussing what exactly freedom means with Makgosi Letimile, a writer, disability activist and sex toy reviewer.

- Sex Workers Speak, in which Nosipho Vidima speaks on creative spaces for street-based sex workers, sex work during a pandemic, and online safety.

- Seeing our bodies in various ways and the feelings that beings.

- A photo essay interrogating anxiety, pleasure and capitalism.

Youlendree believes that the work that they do does benefit the community but finds to difficult to measure. Generally, she says that they feel like the e-zines have benefited African feminists on the internet. The work in their e-zines attempts to speak to people who are at various points in their feminist journey - whether one is a parent wondering how to speak to their children about sex, or a teenager navigating being queer on the internet, or a feminist philanthropist.

The collective believes that part of the work of building power is hearing each other out, and that is one of the first things that they set out to do. Ruth, an ecofeminist, repeatedly drew their attention towards considering the sources of hardware for the technology that they use (including the technology that was making these conversations possible) by asking — whose feminist internet is it anyway, if its creation and proliferation demands the simultaneous exploitation of people, their labour and their land?

They felt that this question was applicable to everyone’s lives. Every collaborator on this project shared their own perspectives on access to public spaces and resources, all of which were significantly hindered by past, ongoing and expected experiences of gender-based violence.

We talked about the different factors necessary to ensure our safety and that of our communities and movements, and the critical imagination and healing justice that is necessary to bring all our different labours together towards the common goal of freedom.

This e-zine is an exercise of archiving, creativity and cementing the place of those who are marginalised at the centre. It is an assertion of the place of telling our own stories and allowing others who may not have the platforms to do the same the skills and confidence to participate in collating the history of the time we’re currently living in.

- Log in to post comments